|

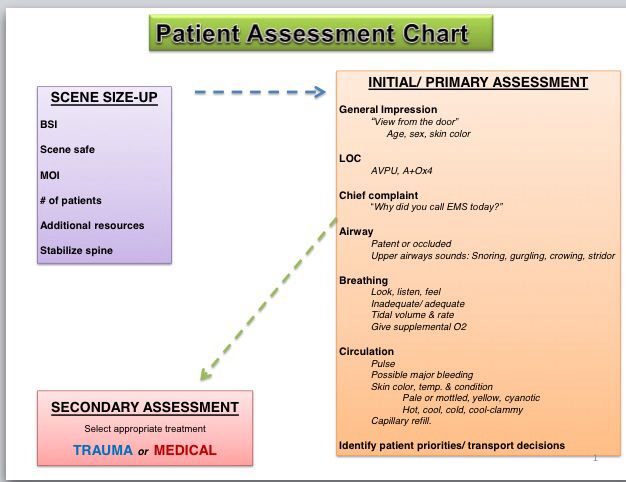

Well, not quite a million, perhaps. But a lot. If you've ever had the need for an EMT's help, you've probably experienced the barrage of questions we ask. And we consider it a really good start when you're awake, alert, and able to answer those questions. Before our EMT classwork can start to talk about interventions for specific injuries or illnesses, it's important for us to identify what, exactly, we're dealing with. And while it's often easy to get the basics when you have a conscious and lucid patient, that isn't always the case. EMTs are drilled to take a specific step-by-step approach, called assessments, in order to ensure we first focus on critical life-threats, and then (and only then) identify and prioritize other issues our patients may be having. These assessments break down to the Primary Assessment (done when we first arrive on the scene), the Secondary Assessment (which may be done on scene, in the ambulance), and re-assessments as needed or warranted by the specific issues and interventions being undertaken. At this point in my EMT course work, we're starting to practice these assessment skills, linking signs and symptoms to the knowledge of anatomy we've been learning, before we move and transport patients anywhere else. And it comes with learning a bunch of mnemonics, such as AVPU, SAMPLE/OPQRST, and DCAP-BTLS (just to name a few), to ensure we don't miss any critical information. Our checklists actually start before we even see the patient, learning how to do a scene size-up in order to ensure our own safety and that of our fellow EMTs. This can include making basic determinations regarding the type of Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) we should be wearing, from gloves and eye protection, to masks, gowns or full-body coverings. Even stuff like taking off our gloves is practiced in our drills, and we corrected by the instructors if we fail to ask about scene safety even in classroom-like practice settings. It also includes determining the Nature Of Illness (NOI) or Mechanism Of Injury (MOI), as well as the number of patients (such as at a car accident, where there may be multiple parties involved). These lead us to determining whether we need additional resources including Paramedics, Fire, Hazmat or additional EMTs. Finally, scene size-up concludes by making a quick determination of the potential for any C-Spine (cervical spine, aka your neck) injuries the patient(s) may have, and taking appropriate precautions to ensure we do no further harm while assessing or moving them. Once these basics are covered, we're being taught to run through the Primary Assessment quickly (but thoroughly) in order to reach a critical decision point - does this patient have life threats that require immediate interventions or transport, or can we take time to do more thorough assessment and investigation of factors contributing to their condition? Primary Assessment starts with our own critical observation: Sick or Not Sick? By itself, being injured doesn't mean that a life-threat exists, but a patient that "looks sick" should guide us towards greater awareness of the Golden Period (and the associated Platinum 10 minutes) during which pre-hospital interventions and care can have the greatest positive impacts. Regardless of whether a patient is alert or unconscious, we're being trained to start with this gut-check question.

Of course, a conscious and alert patient can tell us why they called 911 for help. Sometimes, we have to get that information from family members or even bystanders who may have witnessed or even just randomly came across an individual needing help. Obtaining the Chief Complaint is the next step in our assessment, but it's just another data point in the process. From here, we're being drilled to check the "A-B-C-D-E's", which guides us to cover the critical life threats that may exist with someone's Airway, Breathing, and Circulation (the ABC's). We then assess their neurological status (covering Disabilities), and make sure that any injuries or specific body areas that are associated to the chief complaint are or can be Exposed for further examination or to provide care (such as cutting open part of the clothing to expose a wound, in order to control bleeding). Of course, if we find any life-threats along the way, we'll begin treating them immediately, and will request paramedic support as it becomes appropriate to call on their advanced skills and resources. Some of these assessments are done visually (such as observing chest rise as one element of Airway and Breathing assessment, while others are done through touch (referred to as palpitation), such as obtaining a heart rate by measuring a pulse as part of assessing Circulation). And others may be done by hearing (or auscultation). such as listing for breath sounds in the lungs by using a stethoscope. The AVPU mnemonic is taught as a way to assess how alert and responsive a patient is, ranging from Alert, responsive to Verbal stimuli, responsive to Painful stimuli, and Unresponsive. But even an alert patient can still be confused -- we're being instructed to also assess the orientation of an alert patient by asking questions about who they are ("What's your name?"), time ("What year is it? What month?"), place ("Do you know where we are right now? How did you get here?") and event ("Can you tell me how you ended up on the floor? What were you doing before you felt the pain?"). A patient who is able to answer all of these questions is consider "alert and oriented times four", or A&Ox4 in our shorthand speak (yeah, there's a whole new lingo to pick up as well). And while patients may be able to answer these questions correctly, we've been warned to listen for slurring and other signs that mental capabilities have been affected in some manner, as these might indicate a neurological Disability, such as a stroke. Then again, they could just have a really bad accent. We've also been told to ask "Is this normal?" as it is important to avoid jumping to conclusions. The questions don't end here, but the Primary Assessment does. Based on the data we've gathered, we need to decide of immediate transport is warranted, and if so, package the patient for a trip to the hospital Whether we go or stay put a bit longer, more questions will come as we gather baseline vitals and perform a Secondary Assessment, which I'll talk about in a later article.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorJon Alperin, one of our MFAS volunteers, shares his journey to becoming an NJ certified EMT. from the Start

Here is Jon's journey, presented in time order:

Archives

June 2016

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed